Like many federal laws, the No Child Left Behind Act operates mostly on states and local agencies. Few ordinary citizens notice it in their private lives.

But NCLB, the centerpiece of President Bush's compassionate conservatism, has had a deeper impact on the nation's schools and thus on students than any other piece of federal legislation.

"It's changed the conversation in the schools," as Alan Bersin, Gov. Arnold Schwarzenegger's outgoing secretary of education, said the other day, by forcing serious attention on school accountability and achievement, particularly the lagging achievement of poor and minority kids.

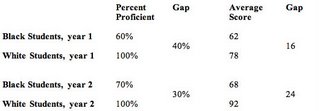

Serious attention, or disingenous political rhetoric? Check out (click to enlarge) this chart by Jerry Bracey:

Serious attention, or disingenous political rhetoric? Check out (click to enlarge) this chart by Jerry Bracey:But it's also generated fundamental controversies and thorny problems that go to the heart of the nation's ambivalence about educational policy and the treatment of kids. One of its two core provisions requires all schools to achieve 100 percent proficiency in major academic fields by 2014. Schools receiving federal funds for disadvantaged students that don't make progress toward that goal face an increasingly tough set of sanctions.

Some critics have called the very notion of 100 percent proficiency an oxymoron -- something that, if proficiency is to have any meaning, can't be achieved. And since the states themselves define proficiency and set their own standards, some, such as Wisconsin, have lowered their standards to make the targets. California, which has among the highest standards in the nation, is not one of them, despite some legislative efforts to water them down.

Professor Schrag does not go so far here as to agree with the critics, even though he doubtless knows they are correct. Studies in MA, WI, MI, IL, for instance, show a 60-90% failure rate by 2014, even with the state standards that Schrag claims have been watered down. If we abandoned state standards for, let’s say, NAEP standards, there would truly be no public school left standing even before 2014 (see Bob Linn’s projections based on NAEP scores (pdf). Of course, no public school left standing (NPSLS) is exactly the result that the education privatizers have been working toward even before the NCLB was craftily crafted, a fact that has been shrouded beneath the threadbare mantle and the cynical mantra of "closing the achievement gap" between rich and poor.

But as seemed evident from the start, the federal mandate on schools to get students in all ethnic, economic and educational subgroups to full proficiency is a near impossibility, especially for learning disabled students and immigrants who have been in U.S. schools for three years -- or perhaps five years -- or less.

Rep. George Miller of Martinez, a Democrat who's the incoming chairman of the House Education Committee, and, with Sen. Ted Kennedy, one of the co-authors of NCLB, agrees that the law needs fixes especially in weighing the achievement of English learners and handicapped students.

He's also willing to consider proposals from California and other states that school progress be measured by year-to-year growth rather than movement toward that 100 percent proficiency goal. But he's leery about abandoning a drop-dead date. "We can't give away the integrity of the act," he said. If the schools think that mere "growth," no matter how little, is enough for students to be competitive in the global economy, the country is likely to be back on the slippery path to mediocrity.

So it is no longer the job of the American free market to make us competitive in the global economy—it has come down to making children in school accountable for whether or not American capitalism maintains its world dominance. And the slippery path to mediocrity? If we were not being constantly reminded by ED, we could certainly wonder where the mediocrity left off or where it became most pronounced.

In terms of the "integrity of the Act," consider the reasoning that anchors the current stupidity:

- NCLB requires 100% proficiency of all children by 2014.

- The disadvantages of English language learners and handicapped students make it impossible for these children to achieve the 100% proficiency target by 2014.

- Therefore, the goal of 100% proficiency by 2014 must be kept in place to preserve “the integrity of the Act.”

SAT Scores 2002 from the College Board

Family Income Verbal/Math Scores

Less than $10,000/year-----417/442

$10,000 - $20,000/year-----435/453

$20,000 - $30,000/year-----461/470

$30,000 - $40,000/year-----480/485

$40,000 - $50,000/year-----496/501

$50,000 - $60,000/year-----505/509

$60,000 - $70,000/year-----511/516

$70,000 - $80,000/year-----517/524

$80,000 - $100,000/year----530/538

More than $100,000/year---555/568

So if we know, without a doubt, that most poor children, immigrant children, and disabled children are going to score, let’s say, 18-20% lower than middle class native-speaking ableist children, why should we treat their disadvantage of income differently than, let’s say, autism, especially when the same disparities in performance result? Why do we acknowledge a psychological disability, a biological disability, or a language disability at the same time we ignore the socioeconomic disability? Does the refusal to acknowledge poverty as a disability allow us to continue our unethical and inhumane testing practices that we could not allow ourselves otherwise?

The bipartisan deal that led to the passage of NCLB in 2001 was based on a combination of rigorous school accountability measures and increased federal funding that would supposedly pay for the increased demands on schools.

Inevitably there's been erosion at both ends of the bargain. States have continually fudged on the law's demand that there be a "highly qualified teacher" in every classroom -- a laudable target but a near impossibility -- and on the proficiency standards. The Bush administration, while increasing funding, has fallen many billions short of its fiscal commitments when the law was passed.

Not surprisingly, there's been push-back from a variety of sources -- from bipartisan legislative committees, from the National Education Association, from some civil rights groups and from educators who believe that the law's pressure on states has led schools to overemphasize drill for tests and the subjects, particularly math and English, that are tested, and to neglect other subjects.

There's also debate about the extent to which federal accountability programs have raised achievement and closed the gaps between different groups of students. And as low-standards states continue to report high levels of success, the gaps between state and national test scores have increased pressure for a system of national standards, even among educational conservatives who generally oppose meddling with what used to be a strict state-local prerogative.

What's certain is that until the federal and state accountability are "harmonized" -- Bersin's term -- there'll be continuing public confusion about what different scores and proficiency reports mean. In California, as elsewhere, hundreds of schools that are doing well according to the state's "growth" model are underperforming in moving toward the federal proficiency target.

Although NCLB is up for renewal this coming year, and while it's already the subject of hearings, the chances of major revisions before the 2008 presidential election -- or even on anything more than a temporary extension -- are low. Given the controversies, neither the administration nor Congress is eager to touch the subject any sooner than necessary.

And yet it's also true that, as Miller says, "When you have poor kids, poor schools and poor teachers, how can you expect a good result?" To change that requires a major -- and well targeted -- investment, including serious reforms in the nation's tired schools of education, another item on Miller's agenda. And it will require a continuing national push.

So will changing the schools of education bring an end to the family income chasm, which is the source of the achievement gap? Who will be blamed after it is demonstrated that schools of education are not creating the gap?

"If NCLB is gone," as he says, "America's poor kids will again be forgotten."

Does Rep. Miller really believe that poor kids have been helped by dumping them into the cruel testing crucible of assured failure? Does he not see that these children are being dumped on the streets the same way they have been dumped ever since slavery—but this time with a new realization that the mantra of “work hard, be nice” means even less than it meant when Booker T. Washington learned it from the white philanthropic liberals of his generation? Will this current generation of assured losers be as acquiescent when they find out they have once again been told a lie that is intended to assure their own complicity in their own subjugation as second-class citizens in a global economic order that doesn’t give a damn about their loss beyond what it might mean to the grand revenue stream that, by the way, continues to carve the canyon between the haves and the have nots.

If Representative Miller’s and Senator Kennedy’s efforts to continue the educational genocide of constant and unrelenting testing in chain-gang schools can be construed as "not forgetting" poor children, then let us assuredly end our memory of them in hopes that our neglect may offer at least an outside chance that these children might survive without the benefit of our obliterating mindfulness.

No comments:

Post a Comment