Left behind by 'No Child Left Behind'…

We have reached a critical crossroads in our educational and

national history. As No Child Left Behind’s (NCLB’s) reauthorization or

expiration takes center stage in Washington, American citizens who care

about the future of our public schools and our democracy must be heard.

Our shared future is not an abstract political possibility but, rather,

one that breathes in every son or daughter, every niece or nephew, every

grandson or granddaughter, every neighbor’s child, and every one of our

own students who enters the schoolhouse door.

While [the Secretary of Education] and legislators from both parties

stubbornly proclaim that NCLB is working [or has been beneficial] —despite of all the empirical

evidence indicating otherwise — and as politicians boast that no child

is being left behind, let us pause

to consider what has been jettisoned. Let us take a moment to think

about what has been left behind, what has been dumped, what has been

pushed out the door because there is no longer space or time for it in

the school day.

Now if your school still has some of these things, I say

congratulations. At the same time, however, I say beware. Beware,

because the unattainable goal of 100 percent proficiency that is the

bedrock of NCLB makes it most likely that over the next seven years,

your school will join the 30 percent [now 60 percent] of schools today where these

crucial elements of school have already been left behind.

As American citizens deeply concerned about the health of our

democratic republic, we are, of course, concerned and horrified that the

social studies have been left behind. In Florida and other states,

social studies teachers, afraid of losing their jobs, are lobbying for

social studies to be tested, so that their work will survive.

The emphasis on math and reading tests has meant less

geography, civics, and government, which leaves children ignorant of how

public decisions are made or where their community fits into state,

national, and global contexts — or even that there is a context beyond

their street and TV screens. Children are left, in effect, stranded on

lonely islands of ignorance, without the impetus or skills to have their

voices heard in ways that make the world listen.

History, too, has been left behind, making it assured that this

next generation will grow up more likely to be swayed by the mistakes

and misdeeds of the past to which they remain clueless. What is a

democratic republic and where did it come from? Sorry, that’s not on the

test, either.

And economics? While children in wealthy communities — the ones

without AYP worries yet — play stock market games and learn about hedge

funds, the economic education of children in schools under the testing

gun consists of collecting “Scholar Dollars” that they trade in for bags

of Skittles, a pittance of pay for a meaningless labor whose

significance remains a mystery to them.

Health and physical education have been left behind, too,

leaving children out of shape and subject to diseases associated with

obesity and inactivity. At the same time, children are left in the dark

about the importance of healthy foods, fresh fruits and vegetables, the

kinds of foods that are scarce in the small stores of poor

neighborhoods. And left behind, too, is information about the hazards of

a never — ending diet of Taco Bell and McDonalds — because that’s not

on the test, either.

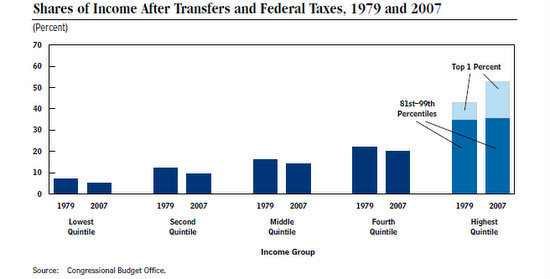

Art and music have been left behind, leaving in their crossing

wakes an imagination gap, a creativity gap, and expression gap, an

aesthetic gap — a souls gap. We can add these gaps to the achievement

gap that parallels a widening economic gap — despite years and years of

increased testing and accountability in those schools where the economic

gaps are at their deepest points.

Diversity of thought has been left behind. What remains in

failing schools and the ones teetering on the testing bubble are

collections of remote and desiccated facts that represent not even a

single culture, but rather, an anti-culture that has essentially

eradicated cultural values as a discussable issue.

Science has been left behind, too, and thus the primary tool

for understanding how the modern world is organized. Where science

survives, it is where it is tested, and the kind of science that remains

is the kind that can be fit into a multiple-choice format, not the kind

that exercises children’s ability to think, solve problems, conduct

experiments, and make good decisions.

Literature has been left behind, and with it the love of

reading and books and the curiosity that is spawned and kept alive by

the life of the imagination. Stories are now substituted by the measured

mouthing of nonsense syllables and the framing of comprehension

responses that the children who utter them do not understand.

Recess has been left behind in a third of all American

elementary schools, and as the percentage of failing schools increases,

we may expect that number to rise. Play, itself, then becomes left

behind, and along with it one of the most useful skills of all—to think

as if, what if, as in what if life were somehow different than, or what

if there were a choice beyond a, b, c, or d?

Nap time has been left behind in kindergarten and even in

pre-K, as teachers focus on replacing dream time with skill practice

time for a future of testing.

Field trips, holidays, and assemblies have been left behind

unless they can be used for test preparation, or unless they come after

the test, those short precious weeks when smiles may be seen to return

to teachers’ lips and to students’ eyes.

The love of the teacher for her craft has been left behind in

so many schools, replaced by the burdensome regimen of the pacing guide

and the production schedule and the script. And time for teacher-led

discussion, exploration, reflection? There is only time for teachers to

learn their lines, trying to become good actors in a very bad play where

the audience is compelled to participate. And time to weigh the results

of the practice tests in order to get ready for the real tests.

Left behind, too, are teacher autonomy and professional

discretion. Now whole hallways of fourth grade classes are on the same

page of the same scripted lesson at the same moment that any supervisor

should walk by, supervisors who are identically trained to look for the

same manifestations of sameness, from bulletin boards to hand signals to

the distance that children are trained to maintain from one another as

they march to lunch, with their arms holding together their imaginary

straightjackets.

Most troubling, however, of all that has been left behind is

the teacher’s nurturing care, the teacher whose advocacy for and

sensitivity to every child’s fragile humanity has been a trademark of

what it means to be the teacher of children. With the current laser focus on avoiding test failure, even as

expectations become higher with each passing year, the child who cannot

do more than a child can do now becomes viewed as the stumbling block to

a success that is increasingly elusive. Instead, then, of being viewed as the reasons we have schools

to begin with, the needful child who is, indeed, behind, becomes the

obstacle to a proficiency that becomes further and further out of reach.

When this occurs, as it surely does every time teachers and principals

fall prey to the pressure, children become the burden that must be

reluctantly borne, obstacles to a success that their own disability,

poverty, or language issues complicate— and that even the best teacher

can never compensate for.

Students, then, come to be seen as complicit in creating the

failure that, in fact, no one, teacher or student, can remedy, because

there is a monstrous system that has made child failure and, thus,

school failure inevitable, a monstrous system that has traded and

treated this generation of children as a means to attain a political

end—a political end that, in fact, threatens our future as a free people

who are able to think, to solve problems, to care, to imagine, to

understand, to have empathy, to participate, to grow, to live.

So as you listen to the growing debate this fall in Washington,

please do not leave your political responsibility behind and your good

sense with it. Go online tonight and order the Linda Perlstein book,

Tested. . .. Read it and, as you do so, keep in mind that the horror

that she so ably describes occurred in a school that is considered a

success, a “lighthouse school.” Think, then, of what it must be like in

the thirty percent [now sixty] of American schools that are now labeled failures.

Recently, a quote by Cal State professor, Art Costa showed up

on one of internet discussion groups, a quote that is horribly relevant

today: “What was once educationally significant, but difficult to

measure, has been replaced by what is insignificant and easy to measure.

So now we test how well we have taught what we do not value.”

Call and write and visit your school boards and your

Congressional delegation. Remind them what you value and what you

believe to be significant for now and for our future, and what you know

that now and finally must to be left behind.

Jim Horn

October 2007

A similar version of this speech was delivered September

27, 2007, at Monmouth University's Pollack Theatre for the Central Jersey chapter of Phi Delta Kappa.

Dana Goldstein is a widely read journalist and a fellow of the

Dana Goldstein is a widely read journalist and a fellow of the