Feb. 28, 2012, 11:18 a.m.I’m delighted that the New York City Education Department has released its teacher data reports.

Finally, there are some solid numbers for judging teachers.

Using a complex mathematical formula, the department’s statisticians have calculated how much elementary and middle-school teachers’ students outpaced — or fell short of — expectations on annual standardized tests. They adjusted these calculations for 32 variables, including “whether a child was new to the city in pretest or post-test year” and “whether the child was retained in grade before pretest year.” This enabled them to assign each teacher a score of 1 to 100, representing how much value the teachers added to their students’ education.

Then news organizations did their part by publishing the names of the teachers and their numbers. Miss Smith might seem to be a good teacher, but parents will know she’s a 23.

Some have complained that the numbers are imprecise, which is true, but there is no reason to be too alarmed — unless you are a New York City teacher.

For example, the margin of error is so wide that the average confidence interval around each rating for English spanned 53 percentiles. This means that if a teacher was rated a 40, she might actually be as dangerous as a 13.5 or as inspiring as a 66.5.

Think of it this way: Mayor Michael R. Bloomberg is seeking re-election and gives his pollsters $1 million to figure out how he’s doing. The pollsters come back and say, “Mr. Mayor, somewhere between 13.5 percent and 66.5 percent of the electorate prefer you.”

There are a few other teensy problems. The ratings date back to 2010. That was the year state education officials decided that their standardized test scores were so inflated and unreliable that they had to use their own complex mathematical formula to recalibrate. One minute 86 percent of state students were proficient in math, the next minute 61 percent were.

Albert Einstein once said, “Not everything that can be counted counts, and not everything that counts can be counted,” but it now appears that he was wrong.

Of course, no one would be foolish enough to think that people would judge a teacher based solely on a number like 37. As Shael Polakow-Suransky, the City Education Department’s No. 2 official, told reporters on Friday, “We would never invite anyone — parents, reporters, principals, teachers — to draw a conclusion based on this score alone.”

Within 24 hours The Daily News had published a front-page headline that read, “NYC’S Best and Worst Teachers.” And inside, on Page 4: “24 teachers stink, but 105 called great.”

The publication of the teacher data reports is a defining moment. A line has been drawn between those who say, “even bad data is better than no data,” and those who say, “Have you no shame?”

Arne Duncan, the federal education secretary, has been a dependable advocate for naming names. In 2010, when The Los Angeles Times printed a similar list of teachers and value-added scores, Mr. Duncan, sounding very much like Winston Churchill, declared, “Silence is not an option.”

The former New York schools chancellor, Joel I. Klein, a leader among educators who consider themselves data-driven, has continued that commitment even after leaving the job. He now works for Rupert Murdoch running Wireless Generation, a company that describes itself as “the leading provider of innovative education software, data systems and assessment tools.”

In 2010, Mr. Klein talked with the radio station WNYC about the importance of teacher data reports. “Any parent I know,” he said, “would rather see a teacher getting substantial value-add rather than negative value-add.”

It was a surprise to see how many data-driven people spoke against making the reports public. Bill Gates, who has spent billions of dollars to bring statistical study to school systems, wrote an Op-Ed page piece published in The New York Times last week that was headlined, “Shame Is Not the Solution.”

Merryl H. Tisch, the chancellor of the State Board of Regents, told The Times, “I believe the teachers will be right in feeling assaulted and compromised here.”

Even Dennis M. Walcott, the city’s current schools chancellor — who usually can be counted on to do what Mr. Klein did — sounded like a man with qualms. “I don’t want our teachers disparaged in any way, and I don’t want our teachers denigrated based on this information,” he said.

At first, when I heard that news organizations were going to publish the list, I was angry, but that has passed. Good has come of this. People have been forced to stop and think about how it would feel to be summed up as a 47, and then have the whole world told.

Michael Winerip writes the On Education column for The New York Times.

Wednesday, February 29, 2012

If The Plan Is to Kill Us With Tests, Then We Will Kill the Tests

Will Arne Duncan Please Answer Valerie Strauss

This was written by Bruce D. Baker, a professor in the Graduate School of Education at Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey. This first appeared on his School Finance 101 blog.

By Bruce D. Baker

Lately it seems that public policy and the reformy rhetoric that drives it are hardly influenced by the vast body of empirical work and insights from leading academic scholars which suggests that such practices as using value-added metrics to rate teacher quality, or dramatically increasing test-based accountability and pushing for common core standards and tests to go with them are unlikely to lead to substantial improvements in education quality, or equity.

Rather than review relevant empirical evidence or provide new empirical illustrations in this post, I’ll refer to the wisdom and practices of private independent schools – perhaps the most market-driven segment and most elite segment of elementary and secondary schooling in the United States.

Really… if running a school like a ‘business’ (or more precisely running a school as we like to pretend that ‘businesses’ are run… even though ‘most’ businesses aren’t really run the way we pretend they are) was such an awesome idea for elementary and secondary schools, wouldn’t we expect to see that our most elite, market oriented schools would be the ones pushing the envelope on such strategies?

If rating teachers based on standardized test scores was such a brilliant revelation for improving the quality of the teacher workforce, if getting rid of tenure and firing more teachers was clearly the road to excellence, and if standardizing our curriculum and designing tests for each and every component of it were really the way forward, we’d expect to see these strategies all over the home pages of web sites of leading private independent schools, and we’d certainly expect to see these issues addressed throughout the pages of journals geared toward innovative school leaders, like Independent School Magazine. In fact, they must have been talking about this kind of stuff for at least a decade. You know, how and why merit pay for teachers is the obvious answer for enhancing teacher productivity, and why we need more standardization… more tests… in order to improve curricular rigor?

So, I went back and did a little browsing through recent, and less recent issues of Independent School Magazine and collected the following few words of wisdom:

From Winter 2003, when the school where I used to teach decided to drop Advanced Placement courses:

A little philosophy, first. Independent schools are privileged. We do not have to respond to the whims of the state, nor to every or any educational trend. We can maximize our time attuned to students and how they learn, and to the development of curriculum that enriches them and encourages the skills and attitudes of independent thinkers. Our founding charters and missions established independence for a range of reasons, but they now give all of us relative curricular autonomy, the ability to bring together a faculty of scholars and thinkers who are equipped to develop rich, developmentally sound programs of study. As Fred Calder, the executive director of New York State Association of Independent Schools, wrote in a letter to member schools a few years ago: “If we cannot design our programs according to our best lights and the needs of our communities, then let the monolith prevail and give up the enterprise. Standardized testing in subject areas essentially smothers original thought, more fatally, because of the irresistible pressure on teachers to teach to the tests.”

Blasphemy? Or simply good education!

And from way, way back in 2000, in a particularly thoughtful piece on “business” strategies applied to schools:

Educators do not respond to the same incentives as businesspeople and school heads have much less clout than their corporate counterparts to foster improvement. Most teachers want higher salaries but react badly to offers of money for performance. Merit pay, so routine in the corporate world, has a miserable track record in education. It almost never improves outcomes and almost always damages morale, sowing dissension and distrust, for three excellent reasons, among others: (1) teachers are driven to help their own students, not to outperform other teachers, which violates the ethic of service and the norms of collegiality; (2) as artisans engaged in idiosyncratic work with students whose performance can vary due to factors beyond school control,teachers often feel that there is no rational, fair basis for comparison; and (3) in schools where all faculty feel underpaid, offering a special sum to a few sparks intense resentment. At the same time, school leaders have limited leverage over poor performers. Although few independent schools have unionized staff and formal tenure, all are increasingly vulnerable to legal action for wrongful dismissal; it can take a long time and a large expense to dismiss a teacher. Moreover, the cost of firing is often prohibitive in terms of its damage to morale. Given teachers’ desire for security, the personal nature of their work, and their comparative lack of worldliness, the dismissal of a colleague sends shock waves through a faculty, raising anxiety even among the most talented.

Unheard of! Isn’t firing the bad teacher supposed to make all of those (statistically) great teachers feel better about themselves? Improve the profession? [that said, we have little evidence one way or the other]

How can we allow our leading private, independent, market-based schools to promote such gobbledygook? Why do they do it? Are they a threat to our national security or our global economic competitiveness because they were not then, nor are they now (see recent issues:http://www.nais.org/) fast-tracking the latest reformy fads? Testing out the latest and greatest educational improvement strategies on their own students, before those strategies get tested on low income children in overcrowded urban classrooms? Why aren’t the boards of directors of these schools — many of whom are leaders in “business” — demanding that they change their outmoded ways? Why? Why? Why? Because what they are doing works! At least in terms of their success in continuing to attract students and produce successful graduates.

Now, that’s not to say that these schools are completely stagnant, never adopting new strategies or reforms. They do new stuff all the time (technology integration, etc.) – just not the absurd reformy stuff being dumped upon public schools by policymakers who in many cases choose to send their own children to private independent schools.

In my repeated pleas to private school leaders to provide insights into current movements in teacher evaluation and compensation, I’ve actually found little change from these core principles of nearly a decade ago. Private independent schools don’t just fire at will and fire often and teacher compensation remains very predictable and traditionally structured. I’d love to know, from my private school readers, how many of their schools have adopted state-mandated tests?

Private independent schools pride themselves on offering small class sizes (see also here) and a diverse array of curricular opportunities, as well as arts, sports and other enrichment – the full package. And, as I’ve shown in my previous research, private independent schools charge tuition and spend on a per pupil basis at levels much higher than traditional public school districts operating in the same labor market. They also pay their headmasters well! More blasphemy indeed.

In fact, aside from “no excuses” charter schools whose innovative programs consist primarily of rigid discipline coupled with longer hours and small group tutoring (not rocket science), and higher teacher salaries (here, here and here) to compensate the additional work, private independent schools may just be among the least reformy elementary and secondary education options out there .

That’s not to say they are anything like “no excuses” charter schools. They are not in many ways. But they are equally non-reformy. In fact, the average school year in private independent schools is shorter not longer than in traditional public schools — about 165 days. And the average student load of teachers working in private independent schools (course sections x class size) is much lower in the typical private independent school than in traditional public schools. But that ain’t reformy stuff at all, any more than trying to improve outcomes of low income kids by adding hours and providing tutoring.

None-theless, for some reason, well educated people with the available resources, keep choosing these non-reformy and expensive schools. Some of these schools have been around for a while too! Maybe, just maybe, it’s because they are doing the right things – providing good, well rounded educational opportunities as many of them have for centuries, adapting along the way.

Perhaps they’ve not gone down the road of substantially increased testing and curriculum standardization, test-based teacher evaluation – firing their way to Finland — because they understand that these policy initiatives offer little to improve school quality, and much potential damage.

Perhaps there are some lessons to be learned from market-based systems. But perhaps we should be looking to those market based systems that have successfully provided high quality schooling for centuries to our nation’s most demanding, affluent and well educated leaders, rather than basing our policy proposals on some make-believe highly productive private sector industry where new technologies reduce production costs to near $0 and where complex statistical models are used to annually deselect non-productive employees.

Just pondering the possibilities, and still waiting for Zuck (an Exeter alum) to invest in Harkness Tables for Newark Public Schools and class sizes of 12 across the board!

Tuesday, February 28, 2012

Why Bill Gates Makes Me Throw Up

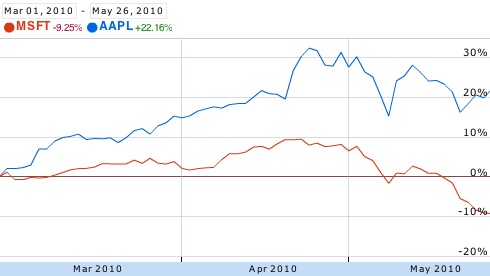

The chart above shows market capitalization trends for Apple and Microsoft over just two months in 2010.

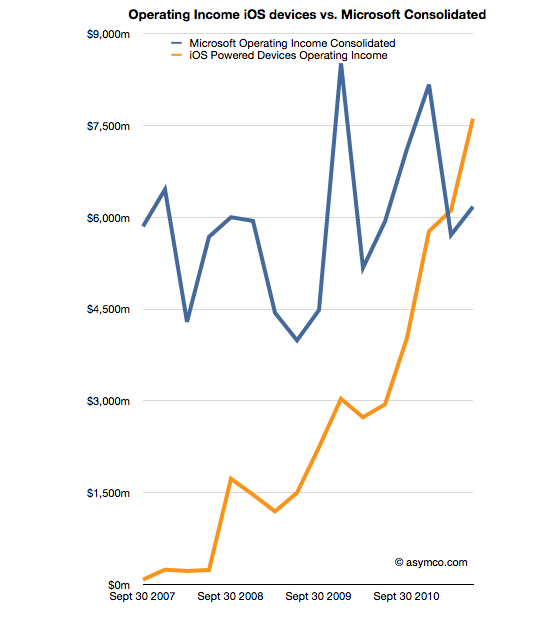

To show that this trend of Microsoft's failing hegemony is not a fluke, here is another showing operating income from devices running Apple and Microsoft systems from 2007 to 2011(click either to enlarge).

So while Bill Gates's company has established its clear descent from the high tech heights in recent years, Bill has plunged into arenas for which he knows even less, though you would never know it based on his consistent levels arrogance, petulance, and patronizing attitudes.

Microsoft's in-house response to its own leadership failure and loss of market share has been to double the percentage of its employees in the lowest rung of company performers (from 10 to 20 percent), cut in half the percentage of top performers (from 20 to 10 percent), and to tie these salaries to their performance levels. In short, punish the workers for the failure of leadership in the company to do anything other than produce crap products.

How does that [KIPP school] compare to a normal school? Well, in a normal school teachers aren’t told how good they are. The data isn’t gathered. In the teacher’s contract, it will limit the number of times the principal can come into the classroom—sometimes to once per year. And they need advanced [sic] notice to do that. So imagine running a factory where you’ve got these workers, some of them just making crap, and the management is told, “Hey, you can only come down here once a year, but you need to let us know, because we might actually fool you, and try to do a good job in that one brief moment.

Monday, February 27, 2012

Common core standards/national tests = a classic grassroots movement?

“The idea that the Common Core standards are nationally-imposed is a conspiracy theory in search of a conspiracy. The Common Core academic standards were both developed and adopted by the states ...” https://www.ed.gov/news/press-releases/statement-us-secretary-education-arne-duncan-1

How can anybody doubt this? The Common Core/National tests movement was a classic spontaneous grass roots movement. Who can forget the many meetings, the sit-ins, the marches and the signs carried by thousands of teachers, students, and parents all over the United States: "Please sir, more tests!" "TESTPREP = EDUCATION!" "Give us standards! ONE SIZE FITS ALL!" "THE HELL WITH PIAGET" "Ours is not to reason why ...."

Sunday, February 26, 2012

Resolution opposing common core standards and national tests

Resolution on National Standards and Tests

Submitted to National Council of Teachers of English, Committee on Resolutions, via e-mail, on October 10, 2011, for consideration during the Annual Convention in Chicago, Illinois.

The movement for national standards and tests is based on these claims: (1) Our educational system is broken, as revealed by US students' scores on international tests; (2) We must improve education to improve the economy; (3) The way to improve education is to have national standards and national tests to reveal whether standards are being met.

Each of these claims is false. (1) Our schools are not broken. The problem is poverty. Test scores of students from middle-class homes who attend well-funded schools are among the best in world. Our mediocre scores are due to the fact that the US has the highest level of child poverty among all industrialized countries. (2) Existing evidence strongly suggests that improving the economy improves the status of families and children's educational outcomes. (3) There is no evidence that national standards and national tests have improved student learning in the past.

No educator is opposed to assessments that help students to improve their learning. We are, however, opposed to excessive and inappropriate assessments. The amount of testing proposed by the US Department of Education in connection to national standards is excessive, inappropriate and fruitless.

The standards that have been proposed and the kinds of testing they entail rob students of appropriate teaching, a broad-based education, and the time to learn well. Moreover, the cost of implementing standards and electronically delivered national tests will be enormous, bleeding money from legitimate and valuable school activities. Even if the standards and tests were of high quality, they would not serve educational excellence or the American economy.

Resolution

Resolved that the National Council of Teachers of English

* oppose the adoption of national standards as a concept and specifically the standards written by the National Governors Association and Council of Chief State School Officers

* alert its members to the counter-productiveness of devoting time, energy and funds to implementing student standards and the intensive testing that would be required.

Carol Mikoda

Susan Ohanian, recipient of NCTE's George Orwell Award for Distinguished Contribution to Honesty and Clarity in Public Language

Stephen Krashen

Joanne Yatvin, NCTE Past President

Bess Altwerger

Richard J Meyer, Incoming president of Whole Language Umbrella

First They Came for the Teachers

“It seems completely wrong,” Ms. Kahn said, adding that one of the co-teachers in the sixth grade did not even get a rating, in an apparent mistake.

Publicly humiliating teachers is wrong but decades of measuring test scores, students and policies like Race to the Top have made it more difficult to discern right from wrong - a dangerous path indeed. It is time to stand up for the New York City teachers and public school teachers all across the country who are being targeted as scapegoats by failed social and economic policies.

MARTIN NIEMÖLLER:

First they came for the Socialists, and I did not speak out --Because I was not a Socialist.

Then they came for the Trade Unionists, and I did not speak out --

Because I was not a Trade Unionist.

Then they came for the Jews, and I did not speak out --

Because I was not a Jew.

Then they came for me -- and there was no one left to speak for me.

In Teacher Ratings, Good Test Scores Are Sometimes Not Good Enough

In Teacher Ratings, Good Test Scores Are Sometimes Not Good Enough

By SHARON OTTERMAN and ROBERT GEBELOFF

At Public School 234 in TriBeCa, where children routinely alight for school from luxury cars, roughly one-third of the teachers’ ratings were above average, one-third average and one-third below average.

At Public School 87 on the Upper West Side, where waiting lists for kindergarten spots stretch to stomach-turning lengths, just over half the ratings were above average. The other half were average or below average on measure, based on student test scores.

And at Public School 29 in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn, where many young parents move to send their children, four of the teachers’ ratings were above average, seven were average and five were below.

The New York City Education Department on Friday released the ratings of some 18,000 teachers in elementary and middle schools based on how much they helped their students succeed on standardized tests. The ratings have high margins of error, are now nearly two years out of date and are based on tests that the state has acknowledged became too predictable and easy to pass over time.

But even with those caveats, the scores still provide the first glimpse to the public of what is going on within individual classrooms in schools. And one of the most striking findings is how much variation there can be even within what are widely considered the city’s best schools, the ones that each September face a crush of eager parents.

At Public School 321 in Park Slope, Brooklyn, for example, 10 teacher ratings were above average, 13 were average and 5 were below. At Public School 89 in TriBeCa, one of six rated math teachers received higher-than-average rankings, a lower rate than in the city as a whole. In many cases, teachers received two career ratings, one for math and one for English.

The principal cause of the wide variation within schools is the methodology of the ratings, which compares teachers with similar student demographics and scores. For teachers in schools with high-achieving students, good test results are often not good enough, at least by the standards set by the formula.

The city acknowledged that the model was “too sensitive” among teachers whose students did either very well or very poorly. That lesson was shared with schools and the state “as it creates a new model for teacher evaluations,” said Matthew Mittenthal, an Education Department spokesman.

The data, for example, showed 73 cases in which teachers whose students produced consistently outstanding test scores — at or above the 84th percentile citywide — were nonetheless tagged as below average. The reason? The formula expected even better results, based on the demographics and past performance of the students.

While the formula is only one aspect of teacher evaluations, the system represents a sea change in that teachers of such high-performing students will be held accountable for student improvement even if their students are far from failing.

In one extreme case, the formula assigned an eighth-grade math teacher at the prestigious Anderson School on the Upper West Side the lowest possible rating, a zero, even though her students posted test scores 1.22 standard deviations above the mean — normally good enough to rank in the 89th percentile. Her problem? The formula expected her high-achieving students to be 1.84 standard deviations higher than the average — roughly the 97th percentile.

Not all teachers who work with the city’s better-off students can be “above average,” said Sean Corcoran, an associate professor of educational economics at New York University who has written about the city’s scores, developed through a system called value-added modeling.

“The value-added measures are controlling for many of these factors,” Mr. Corcoran said, “so even if you just take the top students in the city, there is going to be a full distribution of teachers working with them, from high scoring to low.”

For parents, seeing the rankings of the teachers they know well can be shocking. Vicki Kahn, a parent at Public School 333, the Manhattan School for Children on the Upper West Side, was surprised to see that some of the teachers whom she considers outstanding had poor ratings, including one who routinely sends many of her students to a highly selective middle school.

“It seems completely wrong,” Ms. Kahn said, adding that one of the co-teachers in the sixth grade did not even get a rating, in an apparent mistake.

Anna Rachmansky, whose son is a fifth grader at P.S. 89 in TriBeCa, was visibly stunned upon discovering that a teacher she held in high regard scored in the 10th percentile in math.

“I’m very surprised she would get poor in anything,” Ms. Rachmansky said. “She’s a very strong educator.”

Sandra Blackwood, the co-president of the parent teacher association at Public School 41 in Greenwich Village, said she had little confidence that the data would be meaningful, though she felt it was important to look.

“If it is anything like the school grading system,” she said, “it will probably be highly arbitrary.”

Though parents can get a peek inside school buildings for the first time to see differences among teachers, it does not help if the underlying information is incorrect, Elizabeth Phillips, the principal of P.S. 321, said.

“What people don’t understand is that they are just not accurate,” she said. “We are talking about minute differences in test scores that cause a teacher to score in the lowest percentiles,” like a teacher whom she finds great and who scored in the sixth percentile because her students went to a 3.92 average test score from a 3.97, out of a possible 4.

And that is not to mention one teacher who had test scores listed for a year she was out on child care leave, Ms. Phillips said.

“The only way this will have any kind of a positive impact,” she said, “would be if people see how ridiculous this is and it gives New York State pause about how they are going about teacher evaluation.”

Despite the problems in the data, Dr. Corcoran said he did think the rankings could be useful in conjunction with classroom observations and what a parent already knew about a teacher. “Even if you don’t learn anything about teachers in the middle, which is most of them,” he said, “maybe you can see who the standouts are and who are the lowest performers.”

Alex Vadukul contributed reporting.

This article has been revised to reflect the following correction:

Correction: February 25, 2012

An earlier version of this article misspelled the surname of a parent at Public School 333 as Khan.

Saturday, February 25, 2012

What the U.S. Can Learn from Education in Venezuela

The PBS NewsHour this Friday evening featured a music program that brings music lessons to a few lucky students in low-income neighborhoods in New York City. Modeled on a program in Venezuela, Harmony, supported by private philanthropy, is helping to raise test scores, improving reading and math skills and keeping kids in school. There are "no excuses" for wasting billions of dollars on test prep, data mining and teacher bashing when meaningful programs in the arts and music have a proven track record of results. Meanwhile, the corporate privatizers, our President, Congress and governors all across the country remain tone deaf when it comes to what really works for children. Instead, they continue to blindly perpetuate failed policies that are leaving millions of children behind while robbing them of their futures.

That the kids are getting top scores does not surprise Placido Domingo.

Watch NY Arts Program Brings 'Harmony' to Low-Income Students on PBS. See more from PBS NewsHour.

PLACIDO DOMINGO, musician: Music is mathematics. Everything, it goes into numbers.

A bar can have four, eight, 16, 32 and 64, depending on the speed of the notes. But once you are playing, once you are singing, that disappears. The mathematics stop, and it comes all the feeling.

JOHN MERROW: Harmony is modeled on a highly successful music education program in Venezuela. It's called El Sistema, and it's helped hundreds of thousands of the country's neediest children.

For 36 years, El Sistema has inspired children to stay in school by giving them free instruments and three to four hours of music instruction every day.

PLACIDO DOMINGO: This education, it has been just not only good for music, but good for society and good for all these kids, and they will never dream to be musicians that they are.

JOHN MERROW: With funding provided by the government, El Sistema helps to support the country's 130 children's orchestras and 288 youth orchestras.

Gustavo Dudamel, one of the more celebrated graduates of El Sistema, is now the conductor of the Los Angeles Philharmonic. The program has produced scores of accomplished musicians, but that's not the primary goal.

ANNE FITZGIBBON: In Venezuela, they will refer to their program not as a music program, not as a cultural program, but as a social program, because, first and foremost, that program is about developing the child. It's first about the child. It's second about the music.

JOHN MERROW: Fitzgibbon would like to reach more children with Harmony, but across the country, funding for music and arts programs is tight.

ODELPHIA PIERRE, teacher: Everyone is so focused on the tasks, the reading, the math, that I think somewhere along the line, we think, well, you know what, they don't really need art. They don't really need music.

ANNE FITZGIBBON: What I want people to understand is that music is so much more profound than just standing on the stage and blowing air through a horn. It's about learning to commit yourself to something and learning that if you invest your time and your efforts in something, it's worthwhile, that something really positive will come out on the other end.

WOMAN: Hi, everybody.

JOHN MERROW: Tonight, the Harmony students are learning just how far music can take them as they meet their conductor, Placido Domingo.

PLACIDO DOMINGO: I'm so proud of and happy to be with you today. And what is one of the most beautiful things that we have in common, of course, is music. And how lucky, how lucky you are.

They are just wonderful kids. And I would like to hear them play, you know? And it will be -- I know at what level they might be, but you might be very surprised, you know?

I think they have a beautiful life in front in them with music.

(MUSIC)

New York Teachers "Assaulted and Compromised:" Lawyers Line Up

The current publication of test scores in New York sets a new low for how political whores in Albany and the corporate whores of the media (hello, NYTimes) can join forces to do their ugly work. A clip from the Times:

The ratings, known as teacher data reports, covered three school years ending in 2010, and are intended to show how much value individual teachers add by measuring how much their students’ test scores exceeded or fell short of expectations based on demographics and prior performance. Such “value-added assessments” are increasingly being used in teacher-evaluation systems, but they are an imprecise science. For example, the margin of error is so wide that the average confidence interval around each rating spanned 35 percentiles in math and 53 in English, the city said. Some teachers were judged on as few as 10 students.Education officials cautioned against drawing conclusions from numbers that are meant to be part of a broader equation.“The purpose of these reports is not to look at any individual score in isolation, ever,” Shael Polakow-Suransky, the No. 2 official in the city’s Education Department, said Friday. “No principal would ever make a decision on this score alone, and we would never invite anyone — parents, reporters, principals, teachers — to draw a conclusion based on this score alone.”

Teachers will be rated as “ineffective, developing, effective, or highly effective.” Forty percent of their grade will be based on the rise or fall of student test scores; the other sixty percent will be based on other measures, such as classroom observations by principals, independent evaluators, and peers, plus feedback from students and parents.

But one sentence in the agreement shows what matters most: “Teachers rated ineffective on student performance based on objective assessments must be rated ineffective overall.” What this means is that a teacher who does not raise test scores will be found ineffective overall, no matter how well he or she does with the remaining sixty percent. In other words, the 40 percent allocated to student performance actually counts for 100 percent. Two years of ineffective ratings and the teacher is fired.

The ratings, which began as a pilot program four years ago to improve instruction in 140 city schools, have become the most controversial set of statistics released by the Bloomberg administration. They came out after a long legal battle and amid anguish and protest among educators; on Twitter posts, some compared their release to a modern-day witch hunt.“I believe the teachers will be right in feeling assaulted and compromised here,” Merryl H. Tisch, the chancellor of the State Board of Regents, said in an interview. “And I just think, from every perspective, it sets the wrong tone moving forward.”. . . .

A longer school year? Two responses

We are on the brink of bankruptcy... and he wants a longer school year?

We have the highest poverty rate among industrialized countries, a more powerful predictor of academic success than any other... and it never comes up?

We have only 75 schools out of 600 in OC with fully functioning/staffed libraries... and we are surprised by low reading scores?

He holds his "summit" at a time when teachers are teaching... so he won't get laughed out of the room.

Richard Moore

Don’t lengthen school year; protect students from impact of poverty

The proposal to lengthen the school year ( “O.C. education chief: students need more school,” Feb. 23) is intended to help the US “compete with countries like Japan, Korea and China.” In terms of educational achievement, only one factor is preventing us from doing this, and it is not the length of our school year. The crucial factor is poverty.

Studies show that American students from well-funded schools who come from middle-class families outscore students in nearly all other countries on international tests. Our average scores are less than spectacular because the US has the highest percentage of children in poverty of all industrialized countries (over 21%; in contrast, high-scoring Finland has less than 4%).

Poverty means inadequate nutrition, inadequate health care, exposure to environmental toxins, and little access to books, all of which are strongly associated with lower school performance. If all of our children had the same advantages middle class children have, our test scores would be at the top of the world.

Stephen Krashen

Original article:

http://www.ocregister.com/news/school-341623-students-education.html

Friday, February 24, 2012

Stand with Corey Husic in Demanding an End to Climate Miseducation by Heartland Institute

Diane Ravitch Pt. 2 in New York Review of Books

Last week the New York State Education Department and the teachers’ unions reached an agreement to allow the state to use student test scores to evaluate teachers. The pact was brought to a conclusion after Governor Andrew Cuomo warned the parties that if they didn’t come to an agreement quickly, he would impose his own solution (though he did not explain what that would be). He further told school districts that they would lose future state aid if they didn’t promptly implement the agreement after it was released to the public. The reason for this urgency was to secure $700 million promised to the state by the Obama administration’s Race to the Top program, contingent on the state’s creating a plan to evaluate teachers in relation to their students’ test scores.

The new evaluation system pretends to be balanced, but it is not. Teachers will be ranked on a scale of 1-100.

Teachers will be rated as “ineffective, developing, effective, or highly effective.” Forty percent of their grade will be based on the rise or fall of student test scores; the other sixty percent will be based on other measures, such as classroom observations by principals, independent evaluators, and peers, plus feedback from students and parents.

But one sentence in the agreement shows what matters most: “Teachers rated ineffective on student performance based on objective assessments must be rated ineffective overall.” What this means is that a teacher who does not raise test scores will be found ineffective overall, no matter how well he or she does with the remaining sixty percent. In other words, the 40 percent allocated to student performance actually counts for 100 percent. Two years of ineffective ratings and the teacher is fired.

The New York press treated the agreement as a major breakthrough that would lead to dramatic improvement in the schools. The media assumed that teachers and principals in New York State would now be measured accurately, that the bad ones would be identified and eventually ousted, and that the result would be big gains in test scores. Only days earlier, a New York court ruled that the media will be permitted to publish the names and rankings of teachers in New York City, even if the rankings are inaccurate. Thus, the scene has been set: Not only will teachers and principals be rated, but those ratings can now be released to the public online and in the press.

The consequences of these policies will not be pretty. If the way these ratings are calculated is flawed, as most testing experts acknowledge they are, then many good educators will be subject to public humiliation and will leave the profession. Once those scores are released to the media, we can expect that parents will object if their children are assigned to “bad” teachers, and principals will have a logistical nightmare trying to squeeze most children into the classes of the highest-ranked teachers. Will parents sue if their children do not get the “best” teachers?

New York’s education officials are obsessed with test scores. The state wants to find and fire the teachers who aren’t able to produce higher test scores year after year. But most testing experts believe that the methods for calculating teachers’ assumed “value-added” qualities—that is, their abilities to produce higher test scores year after year—are inaccurate, unstable, and unreliable. Teachers in affluent suburbs are likelier to get higher value-added scores than teachers of students with disabilities, students learning English, and students from extreme poverty. All too often, the rise or fall of test scores reflects the composition of the classroom and factors beyond the teachers’ control, not the quality of the teacher. A teacher who is rated effective one year may well be ineffective the next year, depending on which students are assigned to his or her class.

The state is making a bet that threatening to fire and publicly humiliate teachers it deems are underperforming will be sufficient to produce higher test scores. Since most teachers in New York do not teach tested subjects (reading and mathematics in grades 3-8), the state will require districts to create measures for everything that is taught (called, in state bureaucratese, “student learning objectives”) for all the others. So, in the new system, there will be assessments in every subject, including the arts and physical education. No one knows what those assessments will look like. Everything will be measured, not to help students, but to evaluate their teachers. If the district’s own assessments are found to be not sufficiently rigorous by State Commissioner of Education John King (who has only three years of teaching experience, two in charter schools), he has the unilateral power to reject them.

This agreement will certainly produce an intense focus on teaching to the tests. It will also profoundly demoralize teachers, as they realize that they have lost their professional autonomy and will be measured according to precise behaviors and actions that have nothing to do with their own definition of good teaching. Evaluators will come armed with elaborate rubrics identifying precisely what teachers must do and how they must act, if they want to be successful. The New York Times interviewed a principal in Tennessee who felt compelled to give a low rating to a good teacher, because the teacher did not “break students into groups” in the lesson he observed. The new system in New York will require school districts across the state to hire thousands of independent evaluators, as well as create much additional paperwork for principals. Already stressed school budgets will be squeezed further to meet the pact’s demands for monitoring and reporting.

President Obama said in his State of the Union address that teachers should “stop teaching to the test,” but his own Race to the Top program is the source of New York’s hurried and wrong-headed teacher evaluation plan. According to Race to the Top, states are required to evaluate teachers based in part on their students’ test scores in order to compete for federal funding. When New York won $700 million from the Obama program, it pledged to do this. What the President has now urged (“stop teaching to the test”) is directly contradicted by what his own policies make necessary (teach to the test or be rated ineffective and get fired).

No high-performing nation in the world evaluates teachers by the test scores of their students; and no state or district in this nation has a successful program of this kind. The State of Tennessee and the city of Dallas have been using some type of test-score based teacher evaluation for twenty years but are not known as educational models. Across the nation, in response to the prompting of Race to the Top, states are struggling to evaluate their teachers by student test scores, but none has figured it out.

All such schemes rely on standardized tests as the ultimate measure of education. This is madness. The tests have some value in measuring basic skills and rote learning, but their overuse distorts education. No standardized test can accurately measure the quality of education. Students can be coached to guess the right answer, but learning this skill does not equate to acquiring facility in complex reasoning and analysis. It is possible to have higher test scores and worse education. The scores tell us nothing about how well students can think, how deeply they understand history or science or literature or philosophy, or how much they love to paint or dance or sing, or how well prepared they are to cast their votes carefully or to be wise jurors.

Of course, teachers should be evaluated. They should be evaluated by experienced principals and peers. No incompetent teacher should be allowed to remain in the classroom. Those who can’t teach and can’t improve should be fired. But the current frenzy of blaming teachers for low scores smacks of a witch-hunt, the search for a scapegoat, someone to blame for a faltering economy, for the growing levels of poverty, for widening income inequality.

For a decade, the Bush-era federal law called No Child Left Behind has required the nation’s public schools to test every student in grades 3-8 in reading and mathematics. Now, the Obama administration is pressuring the states to test every grade and every subject. No student will be left untested. Every teacher will be judged by his or her students’ scores. Cheating scandals will proliferate. Many teachers will be fired. Many will leave teaching, discouraged by the loss of their professional autonomy. Who will take their place? Will we ever break free of our national addiction to data? Will we ever stop to wonder if the data mean anything important? Will education survive school reform?