Why is it so difficult sometimes to have a discussion rather than a debate? Why don’t people listen to each other? I learned a long time ago that the real skill in communication was listening. I bet many reading this have learned that as well. So why do we have so much trouble practicing what we have learned?

Why is it so difficult sometimes to have a discussion rather than a debate? Why don’t people listen to each other? I learned a long time ago that the real skill in communication was listening. I bet many reading this have learned that as well. So why do we have so much trouble practicing what we have learned?

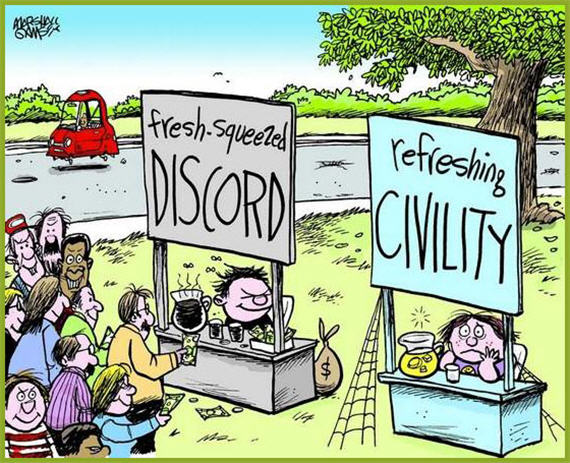

Why do we get so frustrated communicating with various people about issues revolving around public education as well as any number of hot political issues in our increasingly partisan and uncivil society?

I thought I knew. Then I read Jonathan Haidt’s book: The Righteous Mind: Why Good People Are Divided by Politics And Religion.

In a nutshell, actually nine nutshells, here is what I believe can be useful to us all in better understanding communication problems and how to work through them.

These are his words. I have taken his words and put them together in a way I believe makes sense to me and hopefully to others.

THE RIGHTEOUS MIND:

WHY GOOD PEOPLE ARE DIVIDED BY POLITICS AND RELIGION.

- GROUPISH BEHAVIOR: “Our politics is groupish, not selfish.”

Many political scientists used to assume that people vote selfishly, choosing the candidate or policy that will benefit them the most. But decades of research on public opinion have led to the conclusion that self-interest is a weak predictor of policy preferences. Rather, people care about their groups, whether those are racial, regional, religious, or political.

In matters of public opinion, citizens seem to be asking themselves not “What’s in it for me?’ but rather “What’s in it for my group?” Political opinions function as “badges of social membership.” They’re like the array of bumper stickers people put on their cars showing the political causes, universities, and sports teams they support

Individuals compete with individuals, and that competition rewards selfishness—which includes some forms of strategic cooperation. But at the same time, groups compete with groups, and that competition favors groups composed of true team players—those who are willing to cooperate and work for the good of the group. These two processes push human nature in different directions and gave us the strange mix of selfishness and selflessness that we know today.

- HOW WE ARGUE: INTUITIONS COME FIRST, STRATEGIC REASONING SECOND:

- People automatically fabricate justifications of their gut feelings. Rapid and compelling intuitions come first and reasoning is usually produced after a judgment is made to influence other people and for other socially strategic reasons.

– People are only virtuous because they fear the consequences of getting caught—especially the damage to their reputations. People care a great deal more about appearance and reputation than about reality. In fact, the most important principle for designing an ethical society is to make sure that everyone’s reputation is on the line all the time, so that bad behavior will always bring bad consequences. Human beings are really good at holding others accountable for their actions, and we’re really skilled at navigating through a world in which others hold us accountable for our own. When nobody is answerable to anybody, when slackers and cheaters go unpunished, everything falls apart.”

– People are quite good at challenging statements made by other people, but if it’s your belief, then it’s your possession and you want to protect it, not challenge it and risk losing it. Here is some evidence I can point to as supporting my theory, and therefore the theory is right. When we want to believe something, we ask ourselves, “Can I believe it?” Then we search for supporting evidence, and if we find even a single piece of pseudo-evidence, we can stop thinking. We now have permission to believe. We have a justification, in case anyone asks.

– In contrast, when we don’t want to believe something, we ask ourselves, “Must I believe it?” Then we search for contrary evidence, and if we find a single reason to doubt the claim, we can dismiss it.

– If people can literally ONLY see what they want to see, is it any wonder that scientific studies often fail to persuade the general public? And now that we all have access to search engines on our cell phones, we can call up a team of supportive scientists for almost any conclusion twenty-four hours a day. Whatever you want to believe about the causes of global warming just Google your belief. You’ll find partisan websites summarizing and sometimes distorting relevant scientific studies.

– Most of the bizarre and depressing research findings make perfect sense once you e reasoning as having evolved not to help us find truth but to help us engage in arguments, persuasion, and manipulation in the context of discussions with other people. Skilled arguers are not after the truth but after arguments supporting their views. We should not expect individuals to produce good, open-minded, truth-seeking reasoning, particularly when self-interest or reputations are in play.

– But if you put individuals together within a group so that some individuals can use their reasoning powers to disconfirm the claims of others, yet all individuals feel some common bond or shared fate that allows them to interact civilly, you can create a group that ends up producing good reasoning as an emergent property of the social system. This is why it’s so important to have intellectual and ideological diversity within any group or institution whose goal is to find truth (such as an intelligence agency or a community of scientists) or to produce good public policy (such as a legislature or advisory board).

– There are two very different kinds of careful reasoning.

- Exploratory thought is an “evenhanded consideration of alternative points of view.

- Confirmatory thought is “a one-sided attempt to rationalize a particular point of view.

Accountability increases exploratory thought only when three conditions apply:

(1) Decision makers learn before forming any opinion that they will be accountable to an audience

(2) The audience’s views are unknown

(3) They believe the audience is well informed and interested in accuracy.

But the rest of the time—which is almost all of the time—accountability pressures simply increase confirmatory thought. People are trying harder to look right than to be right.

- THREE “ETHICS” EXPLAIN A LOT OF DIFFERENCES:

- The ethic of autonomy is based on the idea that people are, first and foremost, autonomous individuals with wants, needs, and preferences. People should be free to satisfy these wants, needs, and preferences as they see fit, and so societies develop moral concepts such as rights, liberty, and justice, which allow people to coexist peacefully without interfering too much in each other’s projects. If you grow up in a WEIRD (Western, educated, industrial, rich, and democratic) society, you become so well educated in the ethic of autonomy that you can detect oppression and inequality even where the apparent victims see nothing wrong.

- The ethic of community is based on the idea that people are, first and foremost, members of larger entities such as families, teams, armies, companies, tribes, and nations. These larger entities are more than the sum of the people who compose them; they are real, they matter, and they must be protected. People have an obligation to play their assigned roles in these entities. Many societies therefore develop moral concepts such as duty, hierarchy, respect, reputation, and patriotism. In such societies, the Western insistence that people should design their own lives and pursue their own goals seems selfish and dangerous—a sure way to weaken the social fabric and destroy the institutions and collective entities upon which everyone depends.

- The ethic of divinity is based on the idea that people are, first and foremost, temporary vessels within which a divine soul has been implanted. People are children of God and should behave accordingly. If you are raised in a more traditional society, or within an evangelical Christian household in the United States, you become so well educated in the ethics of community and divinity that you can detect disrespect and degradation even where the apparent victims see nothing wrong.

If we look at many issues (The middle East, for instance) through those lenses we can begin to see how we so often cannot hear each other.

– Cultural (and subcultural) variation in morality can be explained in part by noting that cultures can link a behavior to a particular cultural ethic. Should parents and teachers be allowed to spank children for disobedience? On the left side of the political spectrum, spanking typically triggers judgments of cruelty and oppression. On the right, it is sometimes linked to judgments about proper enforcement of rules, particularly rules about respect for parents and teachers.

- FIVE MORAL MATRICES TO UNDERSTAND PARTISANSHIP: CARE, FAIRNESS, LOYALTY, AUTHORITY, AND SANCTITY.”

a. CARE/HARM: The chief moral matrix of liberals in America and elsewhere rests more heavily on the caring for ALL than do the matrices of conservatives. Conservative caring is somewhat different—it is aimed at those who’ve sacrificed for the group. It is not Universalist; it is more local, and blended with loyalty.”

b. FAIRNESS/CHEATING: On the left, concerns about equality and social justice are based in part on Fairness—wealthy and powerful groups are accused of gaining by exploiting those at the bottom while not paying their “fair share” of the tax burden. On the right, the Tea Party movement is also very concerned about fairness. They see Democrats as “socialists” who take money from hardworking Americans and give it to lazy people (including those who receive welfare or unemployment benefits) and to illegal immigrants (in the form of free health care and education).

c. LOYALTY/BETRAYAL: The love of loyal teammates is matched by a corresponding hatred of traitors, who are usually considered to be far worse than enemies. Given such strong links to love and hate, is it any wonder that Loyalty plays an important role in politics?

d. AUTHORITY/SUBVERSION: If authority is in part about protecting order and fending off chaos, then everyone has a stake in supporting the existing order and in holding people accountable for fulfilling the obligations of their station. As with Loyalty, it is much easier for the political right to build on this foundation than it is for the left, which often defines itself in part by its opposition to hierarchy, inequality, and power.

e. SANCTITY/DEGRADATION: Sanctity is crucial for understanding the American culture wars. Why do people so readily treat objects (flags, crosses), places (Mecca, a battlefield related to the birth of your nation), people (saints, heroes), and principles (liberty, fraternity, equality) as though they were of infinite value? Whatever its origins, the psychology of sacredness helps bind individuals into moral communities.

– Liberals are usually more open to experience new foods, new people, music, and ideas. Conservatives prefer to stick with what’s tried and true, and they care a lot more about guarding borders, boundaries, and traditions.

– We see a vast difference between left and right over the use of concepts such as sanctity and purity. American conservatives are more likely to talk about “the sanctity of life” and “the sanctity of marriage.” Sanctity is also used on the spiritual left where many environmentalists revile industrialism, capitalism, and automobiles not just for the physical pollution they create but also for a more symbolic kind of pollution—a degradation of nature, and of humanity’s original nature, before it was corrupted by industrial capitalism.

- REPUBLICANS (Conservatives) UNDERSTAND “MORAL PSYCHOLOGY” MORE THAN DEMOCRATS (Liberals).

– The moral vision offered by the Democrats since the1960s can be seen by many Republican voters (some of whom were once liberal) as too narrowly focused on helping victims and fighting for the rights of the oppressed.

– The political left tends to rest its cases most strongly on Care and Liberty/oppression moral matrices that support ideals of social justice emphasizing compassion for the poor and a struggle for political equality among the subgroups that comprise society. In the contemporary United States, liberals are most concerned about the rights of certain vulnerable groups (e.g., racial minorities, children, animals), and they look to government to defend the weak against oppression by the strong. It leads liberals (but not others) to “sacralize” equality more than liberty, which is then pursued by fighting for civil rights and human rights. Liberals sometimes go beyond equality of rights to pursue equality of outcomes, which cannot be obtained in a capitalist system. This may be why the left usually favors higher taxes on the rich, high levels of services provided to the poor, and sometimes a guaranteed minimum income for everyone.

– Republican morality appealed to all five Moral Matrices. Like Democrats, they can talk about innocent victims (of harmful Democratic policies) and about fairness (particularly the unfairness of taking tax money from hardworking and prudent people to support cheaters, slackers, and irresponsible fools). But Republicans since Nixon have had a near-monopoly on appeals to loyalty (particularly patriotism and military virtues) and authority (including respect for parents, teachers, elders, and the police, as well as for traditions).

– Conservatives, in contrast, are more parochial—concerned about their groups, rather than all of humanity. For them, the Liberty/oppression moral matrix and the hatred of tyranny support many of the tenets of economic conservatism: don’t tread on me (with your liberal nanny state and its high taxes), don’t tread on my business (with your oppressive regulations). American conservatives, therefore, “sacralize” the word liberty, not the word equality. This unites them politically with libertarians. Conservatives hold more traditional ideas of liberty as the right to be left alone, and they often resent liberal programs that use government to infringe on their liberties in order to protect the groups that liberals care most about.”

- LIBERALISM IS AT ODDS WITH BOTH LIBERTARIANS AND CONSERVATIVES: the grand narratives of liberalism and conservatism

The liberal progress narrative: Once upon a time, the vast majority of human persons suffered in societies and social institutions that were unjust, unhealthy, repressive, and oppressive. These traditional societies were reprehensible because of their deep-rooted inequality, exploitation, and irrational traditional “ism. But the noble human aspiration for autonomy, equality, and prosperity struggled mightily against the forces of misery and oppression, and eventually succeeded in establishing modern, liberal, democratic, capitalist, welfare societies. While modern social conditions hold the potential to maximize the individual freedom and pleasure of all, there is much work to be done to dismantle the powerful vestiges of inequality, exploitation, and repression. This struggle for the good society in which individuals are equal and free to pursue their self-defined happiness is the one mission truly worth dedicating one’s life to achieving.

Problem: While Liberals stand up for victims of oppression and exclusion, their zeal to help victims, combined with their low scores on the Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity foundations, often lead them to push for changes that weaken groups, traditions, institutions, and moral capital thus angering Libertarians and Conservatives. This is the fundamental blind spot of the left. It explains why liberal reforms so often backfire, and why communist revolutions usually end up in despotism. It is the reason I believe that liberalism—which has done so much to bring about freedom and equal opportunity—is not sufficient as a governing philosophy. It tends to overreach, change too many things too quickly, and reduce the stock of moral capital inadvertently.

The modern conservative Reagan narrative: Once upon a time, America was a shining beacon. Then liberals came along and erected an enormous federal bureaucracy that handcuffed the invisible hand of the free market. They subverted our traditional American values and opposed God and faith at every step of the way Instead of requiring that people work for a living, they siphoned money from hardworking Americans and gave it to Cadillac-driving drug addicts and welfare queens. Instead of punishing criminals, they tried to “understand” them. Instead of worrying about the victims of crime, they worried about the rights of criminals. Instead of adhering to traditional American values of family, fidelity, and personal responsibility, they preached promiscuity, premarital sex, and the gay lifestyle, and they encouraged a feminist agenda that undermined traditional family roles. Instead of projecting strength to those who would do evil around the world, they cut military budgets, disrespected our soldiers in uniform, burned our flag, and chose negotiation and multilateralism. Then Americans decided to take their country back from those who sought to undermine it.

Problem: Libertarians and Republicans cannot get past their repulsion for their common enemy: the liberal welfare society that they believe is destroying America’s liberty (for libertarians) and moral fiber (for social conservatives).

- CAN PARTISANS UNDERSTAND THE STORY TOLD BY THE OTHER SIDE?

– When liberals try to understand the Reagan narrative, they have a hard time. They actively reject Loyalty, Authority, and Sanctity. They say loyalty to a group shrinks the moral circle; it is the basis of racism and exclusion. Authority is oppression. Sanctity is religious mumbo-jumbo whose only function is to suppress female sexuality and justify homophobia.

– Conservatives score lower on measures of empathy and may therefore be less moved by a story about suffering and oppression. Even though many conservatives opposed some of the great liberations of the twentieth century—of women, sweatshop workers, African Americans, and gay people—they have applauded others, such as the liberation of Eastern Europe from communist oppression. Conversely, Conservatives often fail to notice certain classes of victims, fail to limit the predations of certain powerful interests, and fail to see the need to change or update institutions as times change.

- UNCIVIL POLITICS: We have become Manichean: If you think about politics in a Manichaean way, then compromise is a sin. God and the devil don’t issue many bipartisan proclamations, and neither should you.

– In the last twelve years Americans have begun to move further apart. There’s been a decline in the number of people calling themselves centrists or moderates, a rise in the number of conservatives, and a rise in the number of liberals. Our counties and towns are becoming increasingly segregated into “lifestyle enclaves,” in which ways of voting, eating, working, and worshipping are increasingly aligned. If you find yourself in a Whole Foods store, there’s an 89 percent chance that the county surrounding you voted for Barack Obama. If you want to find Republicans, go to a county that contains a Cracker Barrel restaurant (62 percent of these counties went for McCain).

– We know that much of the increase in polarized politics was unavoidable. It was the natural result of the political realignment that took place after President Lyndon Johnson signed the Civil Rights Act in 1964. The conservative southern states, which had been solidly Democratic since the Civil War (because Lincoln was a Republican) then began to leave the Democratic Party, and by the 1990s the South was solidly Republican. Before this realignment there had been liberals and conservatives in both parties, which made it easy to form bipartisan teams who could work together on legislative projects. But after the realignment, there was no longer any overlap, either in the Senate or in the House of Representatives.

– Things changed for the worse in the 1990s, beginning with new rules and new behaviors in Congress. Friendships and social contacts across party lines were discouraged. Once the human connections were weakened, it became easier to treat members of the other party as the permanent enemy rather than as fellow members of an elite club. Candidates began to spend more time and money on “oppo” (opposition research), in which staff members or paid consultants dig up dirt on opponents (sometimes illegally) and then shovel it to the media. As one elder congressman recently put it, “This is not a collegial body any more. It is more like gang behavior. Members walk into the chamber full of hatred.”

– Nowadays the most liberal Republican is typically more conservative than the most conservative Democrat. And once the two parties became ideologically pure—a liberal party and a conservative party—there was bound to be a rise in Manichaeism. And because since 1995 the vast majority of DC legislators live at home and not in DC, cross-party friendships are disappearing; Manichaeism and scorched Earth politics are increasing.” Other reasons include: include the ways that primary elections are now run, the ways that electoral districts are now drawn, and the ways that candidates now raise money for their campaigns.”

- FIXING INCIVILITY: If you really want to change someone’s mind on a moral or political matter, you’ll need to see things from that person’s angle as well as your own. And if you do truly see it the other person’s way—deeply and intuitively—you might even find your own mind opening in response.

– Empathy is an antidote to righteousness, although it’s very difficult to empathize across a moral divide. The main way that we change our minds on moral issues is by interacting with other people. We are terrible at seeking evidence that challenges our own beliefs, but other people do us this favor, just as we are quite good at finding errors in other people’s beliefs. – – —- When discussions are hostile, the odds of change are slight. But if there is affection, admiration, or a desire to please the other person, then we try to find the truth in the other person’s arguments.

– We all get sucked into tribal moral communities. We circle around sacred values and then share post hoc arguments about why we are so right and they are so wrong. We think the other side is blind to truth, reason, science, and common sense, but in fact everyone goes blind when talking about their sacred objects. If you want to understand another group, follow the sacredness. As a first step, think about the six moral foundations, and try to figure out which one or two are carrying the most weight in a particular controversy.

– If you really want to open your mind, open your heart first. If you can have at least one friendly interaction with a member of the “other” group, you’ll find it far easier to listen to what they’re saying, and maybe even see a controversial issue in a new light. You may not agree, but you’ll probably shift from Manichaean disagreement to a more respectful and constructive yin-yang disagreement.

If you take home solutions, make them these:

- Beware of anyone who insists that there is one true morality for all people, times, and places—particularly if that morality is founded upon a single moral foundation. Anyone who tells you that all societies, in all eras, should be using one particular moral matrix, resting on one particular configuration of moral foundations, is a fundamentalist of one sort or another.

- We all have the capacity to transcend self-interest and become simply a part of a whole. It’s not just a capacity; it’s the portal to many of life’s most cherished experiences.

- The next time you find yourself seated beside someone from another matrix, don’t just jump right in. Establish a few points of commonality or in some other way a bit of trust. And when you do bring up issues of morality, try to start with some praise, or with a sincere expression of interest.

You may not agree with Haidt’s views and research, but try to understand his solutions as you weigh his points and their importance to create civility in our public discourse.

Of course feel free to use them as you post civil comments about this blog post.

Thank you for this. As one of the more vicious polemicists on the side of public education, I do need to be reminded of many of the above points.

ReplyDeleteThere is, however, another dimension to this discussion that I feel deserves consideration. Namely, that critical scholarship finds things such as tone, civility, and the like to be a means of preserving the overarching structural oppressions. Professor Dylan Rodriguez addresses this, saying attempts to confine dialog to that of “white civil society” really confine us in more ways than one. Rather than spend a lot of time trying to flesh this out, I want to say that Professor Paul L. Thomas did a series of essays (I think there’s five in all) on tone. The first one is provided here:

https://radicalscholarship.wordpress.com/2013/09/15/tone-pt-1-does-tone-matter-in-the-education-reform-debate/

I found that Dr. Thomas’ arguments are more cogent and persuasive than any I could make. I do understand that these items aren’t mutually exclusive, but I often find that telling the oppressed to watch their tone, or be civil, is a means of perpetuating their oppressions.